Rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion: a comprehensive review of patient characteristics, presentation patterns, diagnosis, management, and clinical outcomes

Introduction

Dr. M.T. Gallard first described Dieulafoy’s lesion as “miliary aneurysms of the stomach” in 1884 (1). Later on, these lesions were named after a French surgeon, Paul Georges Dieulafoy (1839–1911) who attributed them as “Exulceratio simplex” in 1898 (2). The overall incidence of Dieulafoy’s lesion in the adult population presenting with acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage is approximately 5% (3). Over 70% of all lesions occur in the proximal stomach and 80–95% of gastric lesions are located close to the gastroesophageal junction (3). Moreover, less than 35% of all the cases involve extragastric sites, with duodenum (15%), esophagus (8%), colon (2%), and jejunoileal lesions making up less than 1% (4-6). This disease has a predilection for males in their fifth and sixth decades of life, with the overall male-to-female ratio of 2:1 (6). Although conventional endoscopy remains initial investigation of choice, variable combinations of push enteroscopy and wireless capsule endoscopy can be employed. Angiography, red-cell scan, and intraoperative endoscopy via exploratory laparotomy can be useful in difficult-to-diagnose cases (6). Endoscopic procedures like sclerotherapy, thermal probes, band ligation, and hemoclipping are the cornerstone of management and portend favorable short- and long-term prognoses in most cases (7). In patients with massive life-threatening hemorrhage and hemodynamic instability, angiographic embolization or an open surgical approach can be life-saving (7). With the advancements in endoscopy, the mortality rate has significantly decreased mainly due to early diagnosis and circumventing the complications caused by open surgery (7).

Rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion was first reported by Franko et al. in 1991 (8). Since then, it remained an unusual entity with only 25 cases described till 2007 (9). Currently, rectal lesions account for less than 2% of all Dieulafoy’s lesions, still making it an extremely rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding (10). Therefore, published medical literature lacks extensive and organized data regarding this disease. The purpose of this comparative review is to summarize the patient demographics, presentation patterns, diagnostic investigations, therapeutic modalities, and clinical outcomes of rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion. This article prompts gastroenterologists to remain vigilant in identifying and reporting this disease, especially in patients presenting with hemodynamic instability secondary to gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

Materials and methods

We conducted a systematic literature search to retrieve available data on rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion using the MEDLINE (PubMed, Ovid), Cochrane, Embase, and Scopus databases. Several controlled vocabulary search terminologies (Medical Subject Headings [MeSH] and Embase Subject Headings [Emtree]) such as “Dieulafoy’s lesion”, “rectum”, “Dieulafoy-like”, “anorectum”, and “rectal Dieulafoy lesion” were combined using the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” with the terms “diagnosis”, “treatment”, and “outcomes”. The search was performed without a defined time filter, with language limitation to English-only articles. Furthermore, a manual search was also performed using the reference list of all accessed publications through the above-mentioned strategy. We initially screened titles and abstracts of all retrieved papers to determine their relevance to our topic. The same protocol was used to screen the selected articles for full texts to assess the availability of data. The inclusion criteria for the final comparative analysis consisted of articles describing relevant cases of rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion in the English language that were also available in the full-text form. We presented descriptive data as mean ± standard deviation, median (range), or percentage, as applicable.

Results

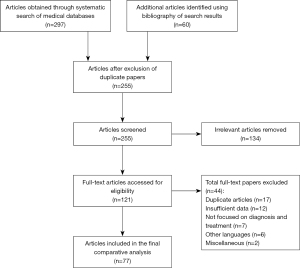

A total of 357 articles consisting of but not limited to original articles, case series, and case reports were initially obtained using the aforementioned search methodology. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, a total of 236 papers were excluded as they were not related to our topic, were in a language other than the English, and/or full-text versions were not available, whereas 121 articles were first enlisted for re-review. After further exclusion of duplicate and redundant articles, 77 papers were included in the present study for the final comparative review (Figure 1). A thorough reading of these articles yielded a total of 101 cases of rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion. The data on individual cases regarding patient demographics, diagnosis, management, and clinical outcomes are summarized. We divided the data into three categories according to the year of publication. First group consisted of patients from 1991 till 2003 (Table S1). The second group included cases from the 2004 till 2012 (Table S2). Similarly, third group contained cases of rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion from 2014 till 2019 (Table S3).

Discussion

Patient characteristics

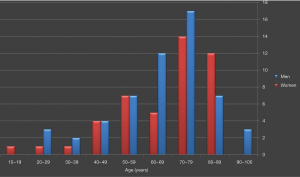

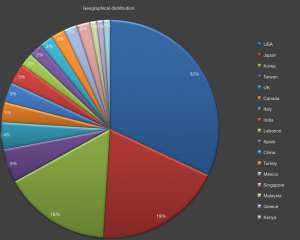

In patients with Dieulafoy’s lesion of the rectum, demographic features correlated with Dieulafoy’s lesions from the other parts of gastrointestinal tract. A comprehensive review of the cases of rectal disease indicated a slight male predominance (males, n=55; females, n=46), with the male-to-female ratio of 1.2:1. The age of the patients ranged from 18 to 94 years (mean ± standard deviation, 66±17 years; median, 71 years). Rectal disease frequently involved patients in their seventh (n=31) and eighth (n=19) decades of life (Figure 2). Although a fixed geographical distribution was not evident, a vast majority of cases included in this review were reported in the developed world (Figure 3). Generally, higher detection rates in these countries/regions can be attributed to the technical advancements in diagnostic modalities.

Pathogenesis

Dr. Dieulafoy initially believed that the lesion was an early stage of a gastric ulcer, with its growth interrupted by the hemorrhagic event (2). In prior studies, it was speculated that gastric arterial aneurysm leads to the development of this lesion, which was occasionally associated with arteriosclerosis. Congenital and acquired vascular malformations have also been considered as plausible etiological factors (3). In current times, it is a general consensus that a Dieulafoy’s lesion is an unusually large, caliber-persistent artery (4,5). The vessel has a diameter of 1.0–3.0 mm and assumes a submucosal tortuous course (6). This artery approaches the mucous membrane and hemorrhage occurs due to erosion of the exposed vascular wall. One theory of spontaneous bleeding highlights the possibility of shear stress caused by compressive arterial pulsations, culminating in mucosal ischemia and subsequent erosion (6,11). Another theory suggests arterial thrombosis as the cause of ischemia and bleeding (12).

Rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion shares gross pathological and histological peculiarities with lesions located in other segments of the gastrointestinal tract (13). However, regional, anatomical, and functional differences between lower and upper gastrointestinal segments can play a role either in the genesis or exacerbation of an existing congenital lesion (14). Stercoral damage due to constipation, inspissated fecal matter, chronic immobilization, cancer, and senile degenerative changes in the vascular and submucosal beds can be mechanical inciting factors for the erosional mechanisms behind bleeding rectal lesions (15-19). Furthermore, mucosal atrophy attributed to senile changes can also be contributory to this process (20). In Dieulafoy’s lesion of the rectum, anal receptive intercourse may also be considered as a potential pathogenetic factor, especially in relatively younger patients with no significant medical conditions (21).

Clinical presentation

Patients with Dieulafoy’s lesion are typically asymptomatic before presenting with acute, profuse gastrointestinal hemorrhage (22). The clinical presentation of rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion is frequently varied as it encompasses a spectrum ranging from episodic self-limited bleeding to massive life-threatening hemorrhage (23). In this review, patients commonly presented with sudden, massive bright-red blood per rectum (47%), hematochezia (36%), painless rectal bleeding (11%), melena (4%), or with variable combinations of above-mentioned forms of lower gastrointestinal bleeding (24-28) (Table 1). Sudden hemodynamic compromise, lower abdominal pain, loss of consciousness, acute stroke, and iron-deficiency anemia were among the other notable presenting clinical features (9,29-34). Several patients were admitted to the hospital for causes other than the gastrointestinal hemorrhage. They either experienced bleeding from rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion during their hospital stay or were diagnosed on incidental colonoscopy performed as a part of the diagnostic workup of other medical conditions (35-40). The bleeding episodes in a number of cases were mild and self-limiting. However, a few patients were identified with an intermittent and massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage leading to severe hemodynamic compromise, necessitating urgent management (41-44). Moreover, hemodynamic status is important as it not only requires urgent detection of the culprit bleeder but also guides appropriate therapeutic approach. Therefore, presentation patterns in patients with rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion are a harbinger for the duration of gastrointestinal hemorrhage, overall condition of the patients, and diameter of bleeding artery (45).

Table 1

| Clinical presentations | N [%] |

|---|---|

| Lower gastrointestinal bleeding | |

| Bright-red blood per rectum | 47 [47] |

| Hematochezia | 36 [36] |

| Painless rectal bleeding | 11 [11] |

| Melena | 4 [4] |

| Admitted with other medical conditions | 16 [16] |

| Hemodynamic compromise | 5 [5] |

| Sudden change in conscious status | 4 [4] |

| Blood loss anemia | 4 [4] |

| Shortness of breath | 3 [3] |

| Abdominal pain | 3 [3] |

Comorbid conditions

Dieulafoy’s lesion has typically been associated with several chronic medical conditions. It is an interesting observation that a history for gastrointestinal disorders is frequently negative in these patients. However, at presentation, either recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding or a dramatic episode of massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage is the clinical phenomenon. A correlation between non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aspirin, and warfarin use has been identified in the past (6,22,46). Published medical literature shows that such patients commonly require NSAIDs and/or anticoagulants for various medical conditions. As expected, the administration of these medications potentially increases the risk for prolonged and severe gastrointestinal hemorrhage. In patients with rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion, hypertension (29%), diabetes mellitus (21%), chronic renal disease (16%), cancer (14%), ischemic heart disease (11%), and prior cerebrovascular accident (11%) were among the common comorbid conditions (47-50).

Mechanical pathologies like constipation and fecalith have also been implicated as a risk factor for gastrointestinal bleeding in these patients (51-53). Mechanical pressures coupled with direct erosive mechanisms are considered in this regard. In concordance with the gastric and duodenal Dieulafoy’s lesion, gastroenterological surgery also precipitated bleeding in a number of patients with rectal disease, indicating the stress injury as a probable inciting factor (6). Alcohol use disorder was another frequently found underlying entity in patients with rectal lesions. However, it is notable that the exact effects of alcohol and tobacco on Dieulafoy’s lesion remain to be determined. Hemorrhoids, hepatic cirrhosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dementia, sigmoid diverticula, and diverticulosis were among the less commonly associated medical conditions (54-56) (Table 2). Rare associations of rectal disease included burns, rectal mucous fistula, and deep venous thrombosis (57-60). Anal receptive intercourse may also be considered as a factor that can increase the propensity of bleeding from rectal lesions (21). Furthermore, there may be increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding due to rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion in patients undergoing therapy with cyclophosphamide, possibly following impaired tissue repair (61,62). However, direct association between immunosuppression and Dieulafoy’s lesion requires further research.

Table 2

| Comorbid conditions | N [%] |

|---|---|

| Hypertension | 29 [29] |

| Diabetes mellitus | 21 [21] |

| Chronic kidney disease | 16 [16] |

| Cancer | 14 [14] |

| Prior cerebral vascular accident | 11 [11] |

| Ischemic heart disease | 10 [10] |

| Constipation | 9 [9] |

| Gastroenterological surgery | 6 [6] |

| Alcohol use disorder | 6 [6] |

| Hemorrhoids | 5 [5] |

| Liver cirrhosis | 3 [3] |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 3 [3] |

| Dementia | 3 [3] |

| Sigmoid diverticula | 2 [2] |

| Diverticulosis | 2 [2] |

Diagnosis

Rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion may pose a significant diagnostic challenge in certain cases. This is mainly due to their small size, relatively inconspicuous nature, and ability to cause intermittent hemorrhage. It may also masquerade as other common vascular abnormalities, such as arteriovenous malformations or vascular aneurysms (6,63,64). In cases with no active bleeding, endoscopic evaluation may reveal the lesion as a nipple-like protrusion, polyp or an exposed vessel, without overlying ulceration or erosion (65-68). However, aberrant culprit arteries are predominantly visualized only during active bleeding (69,70). It is observed that the lesion can also be covered with a blood clot following a prior bleeding episode. Therefore, careful suctioning and proper irrigation may help in such cases (71,72). These factors constitute a significant diagnostic dilemma that may culminate in increased complications in patients with Dieulafoy’s lesion compared to other etiologies of gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy is the initial modality of choice due to its widespread availability and easy use. The endoscopic criteria have been formulated to diagnose patients with Dieulafoy’s lesion: (I) active arterial oozing or micropulsatile, intermittent bleeding from small (<3 mm) mucosal defects, with no ulceration or erosion of surrounding mucosa; (II) visual evidence of raised nipple-like artery; (III) blood clots with a visible tiny point of mucosal attachment (73). In this review, all patients fulfilled the above-mentioned endoscopic diagnostic criteria.

The final diagnostic yield of endoscopy is 70%; however, initial examination with this modality may not be remarkable in all cases. In a study by Reilly and al-Kawas, only 49% of bleeders were detected on initial endoscopy, 33% of patients required a second endoscopic examination, and 18% necessitated exploratory laparotomy to identify the Dieulafoy’s lesion (74). In our analysis of rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion, colonoscopy failed to diagnose 9% of patients and surgical exploration was required for etiology establishment. Yoshikumi et al. demonstrated that the average number of colonoscopies needed for the detection of rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion was 1.7±0.9 (75). In our data, the average number of colonoscopies required was 1.5±0.7, indicating improvements in endoscopic diagnosis of rectal disease. Although poor bowel preparation and stagnant blood contribute to potential dilemma encountered in patients with lower gastrointestinal Dieulafoy’s lesion, an initial thorough endoscopic examination is imperative in patients with rectal lesions.

Radiological investigations, such as computed tomography angiography (CTA), contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (CEMRI), and multidetector-row computed tomography (MDCT) were rarely used to pinpoint the rectal lesions (76-79). The findings of these investigations were subsequently validated by colonoscopy. Therefore, these modalities can be helpful when an initial colonoscopy is nondiagnostic for colorectal Dieulafoy’s lesion. Furthermore, endoscopic ultrasonography may also be performed to establish the diagnosis in selected cases (80).

Management

Until 1990, surgical intervention was the mainstay of treatment for Dieulafoy’s lesion and was associated with a mortality rate up to 80%. In 1990, Goldenberg et al. proposed endoscopic therapy for primary hemostasis in these patients, which has gradually decreased mortality rate to 8% (81,82). The therapeutic endoscopy has evolved into a feasible, safe and effective modality with a hemostatic success rate reported between 75% and 100% (82). For rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion, Abdulian et al. first described endoscopic management (13). In our review, of the 101 reported cases of rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion, patients were initially treated with endoscopic therapy in 81 cases, surgical suturing alone in 12, angiographic embolization in 4, and a combination of endoscopic modalities and surgical ligation in 4 patients. The overall primary hemostasis rate was 87% (88 of 101), with a rebleeding rate of 13% (13 of 101) (Table 3).

Table 3

| Therapeutic modality | Primary hemostasis rate, n [%] | Rebleeding rate, n [%] |

|---|---|---|

| Electrocoagulation | 1/1 [100] | 0/1 [0] |

| Heater probe | 2/2 [100] | 0/2 [0] |

| Gauze tamponade | 2/2 [100] | 0/2 [0] |

| Sclerotherapy (epinephrine, ethanol, tetradecyl sulfate) | 4/6 [67] | 2/6 [33] |

| Band ligation | 9/11 [82] | 2/11 [18] |

| Hemoclipping | 18/20 [90] | 2/20 [10] |

| Combination endoscopic therapy | 35/39 [90] | 4/39 [10] |

| Angiographic embolization | 2/4 [50] | 2/4 [50] |

| Endoscopic therapy followed by surgical ligation | 4/4 [100] | 0/4 [0] |

| Direct surgical ligation | 11/12 [92] | 1/12 [8] |

Based on analysis of this data, endoscopic mechanical therapy, which was used in 49 of 101 patients, showed relatively better therapeutic outcomes. It was either applied as endoscopic monotherapy using hemoclipping or banding alone, or in combination with epinephrine (83-87). Recent literature demonstrates that hemoclipping and band ligation both were equally effective ways of achieving hemostasis in Dieulafoy’s lesions (88). In patients with rectal lesions, Park et al. considered endoscopic band ligation as the preferred therapy (53). On the contrary, Kim et al. suggested that band ligation carried a number of risks and disadvantages, associated with rebleeding in patients with rectal disease (86). In this review, endoscopic hemoclipping with or without epinephrine in comparison to band ligation with or without epinephrine, achieved a higher primary hemostasis rate (91% vs. 79%) and a lower rebleeding rate (9% vs. 21%), respectively. Therefore, endoscopic hemoclipping may have a slight therapeutic superiority over banding for rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion. However, it is notable that patients who received hemoclipping (n=35) as therapy were more than the ones who were treated with band ligation (n=14). Thus, mechanical therapy is feasible, safe, quick and has good long-term results. Future research should compare the efficacies of hemoclipping and band ligation for rectal disease in large patient cohorts to designate either one as the best endoscopic choice.

Meister et al. reported 3 adult patients with rectal Dieulafoy’s lesions who were successfully treated with endoscopic combination therapy using epinephrine and heater-probe coagulation methods (17). In our review, epinephrine plus electrocoagulation in 7, and epinephrine plus heater probe were employed in 4 cases (Table 4). The outcomes of these methods were comparable to endoscopic mechanical therapy. However, mechanical endoscopic techniques appeared to be more feasible and were used in the majority of patients with rectal disease. In this data, repeat therapeutic endoscopy was applied in 10 of 13 patients with rectal disease who experienced rebleeding, which eventually resulted in 100% hemostasis rate. Repeat endoscopic approaches that were used included epinephrine plus heater probe (n=2), endoscopic hemoclipping (n=2), ethanol plus tetradecyl sulphate (n=1), electrocoagulation (n=1), epinephrine plus endoscopic band ligation (n=1), endoscopic hemoclipping plus endoscopic band ligation (n=1), endoscopic band ligation (n=1), and polidocanol (n=1).

Table 4

| Combination of endoscopic modalities | Primary hemostasis rate, n [%] | Rebleeding rate, n [%] |

|---|---|---|

| Epinephrine + endoscopic hemoclipping | 14/15 [93] | 1/15 [7] |

| Epinephrine + electrocoagulation | 6/7 [86] | 1/7 [14] |

| Epinephrine + heater probe | 3/4 [75] | 1/4 [25] |

| Epinephrine + endoscopic band ligation | 2/3 [67] | 1/3 [33] |

| Endoscopic hemoclipping + site tattooing | 2/2 [100] | 0/2 [0] |

| Epinephrine + endoscopic hemoclipping + site tattooing | 2/2 [100] | 0/2 [0] |

| Epinephrine + ethanol | 2/2 [100] | 0/2 [0] |

| Ethanol + electrocoagulation | 1/1 [100] | 0/1 [0] |

| Epinephrine + polidocanol | 1/1 [100] | 0/1 [0] |

| Epinephrine + 50% glucose water | 1/1 [100] | 0/1 [0] |

| Heater probe + endoscopic band ligation | 1/1 [100] | 0/1 [0] |

Radioscintigraphy and angiography are inferior to colonoscopy in localization and treatment of a lower gastrointestinal bleed. However, they can be of use in hemodynamically unstable patients with brisk bleeding, precluding adequate preparation or failed colonoscopy. Angiography can localize the source of bleeding in 25–70% of cases and is therapeutically effective in 40–89% cases of non-diverticular bleeding (89). In our review, angiographic embolization was performed in four cases. Two patients were successfully treated with this modality while the other two required surgery for definitive hemostasis (57,90-92).

Surgical intervention is the ultimate method for achieving hemostasis in patients with rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion. The common surgical techniques are wide-wedge resection or wide oversewing of culprit artery. Atallah et al. also used transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) to perform suture ligation of the rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion (93). In our review, 4 patients required surgery after failed initial therapeutic attempts, whereas 12 patients underwent direct surgical ligation or resection of the bleeding rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion. Of 16 patients, 15 achieved adequate hemostasis with surgery.

Clinical outcomes

In this review of rectal cases (n=101), clinical outcomes were comparable. A total of 6 patients died due to varied causes such as pneumonia (n=2), multiorgan failure (n=2), tumor progression (n=1), and withdrawal of care (n=1). Out of the 101 patients studied, 13 experienced recurrent bleeding. Notably, all of these patients achieved hemostasis with repeat treatment. Thus, it may be speculated that rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion bear a relatively better prognosis and lower recurrence rate, assuming appropriate management is undertaken early in the course of the hemorrhage. However, we acknowledge the limitation of this review as the data were gained mainly from case reports and small case series.

Follow-up

Despite the undeniable benefits of endoscopic therapy, the data on long-term follow-up of rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion is sparse. Therefore, the follow-up duration and methodology generally vary from case to case. In few patients, surveillance colonoscopy was performed in first 24 hours to assess the efficacy of treatment applied and to decipher recurrence of bleeding. After initial intervention to secure hemostasis, the time period to encounter recurrent hemorrhage was varied. Although rebleed occurred in only a few hours of first treatment attempt in a few patients (n=3), it was mostly after 3–7 days (n=8). Out of the total 101 patients, long-term follow-up was documented in 46 patients, with a mean duration of 12 months (range, 1–72 months).

Conclusions

While rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion remains uncommon, it is none-the-less an important cause of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Due to the intermittent nature of bleeding, diagnostic investigations may have their limitations. Gastroenterologists should maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for this etiology. An updated knowledge of the lesion and its presentation patterns can help early detection, which can then lead to timely improvisation of endoscopic or surgical management, ultimately improving clinical outcomes. Standard therapeutic guidelines for rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion are not available. The data presented here favor the use of endoscopic mechanical therapy as relatively effective in such patients. Future research should aim to stratify the efficacy of commonly used endoscopic methods to devise an optimal approach to achieve primary hemostasis. Furthermore, population-based registries should be created in order to systematically organize the patient data regarding Dieulafoy’s lesion of the rectum.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tgh.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tgh.2020.02.17/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Gallard MT. Aneurysme miliaires de l’estomach, donnant lieu a des hematemese mortelles. Bull Soc Med Hop Paris 1884;1:84-91.

- Dieulafoy G. Exulceratio simplex. L'intervention chirurgicale dans les hematemeses foudroyantes consecutives a l'exulceration simple de l'estomac. Bull Acad Med 1898;49:49-84.

- Nojkov B, Cappell MS. Gastrointestinal bleeding from Dieulafoy's lesion: Clinical presentation, endoscopic findings, and endoscopic therapy. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015;7:295-307. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Inayat F, Ullah W, Hussain Q, et al. Dieulafoy's lesion of the oesophagus: a case series and literature review. BMJ Case Rep 2017; [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Inayat F, Amjad W, Hussain Q, et al. Dieulafoy's lesion of the duodenum: a comparative review of 37 cases. BMJ Case Rep 2018;2018:bcr2017223246. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baxter M, Aly EH. Dieulafoy's lesion: current trends in diagnosis and management. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010;92:548-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Norton ID, Petersen BT, Sorbi D, et al. Management and long-term prognosis of Dieulafoy lesion. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;50:762-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Franko E, Chardavoyne R, Wise L. Massive rectal bleeding from a Dieulafoy's type ulcer of the rectum: a review of this unusual disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1991;86:1545-7. [PubMed]

- Baccaro L, Ogu S, Sakharpe A, et al. Rectal Dieulafoy lesions: a rare etiology of chronic lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Am Surg 2012;78:E246-8. [Crossref]

- Enns R. Dieulafoy's lesions of the rectum: a rare cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Can J Gastroenterol 2001;15:541-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ajay G, Mohnish C. Anorectal Dieulafoy's lesion. Indian J Surg 2006;68:325-7.

- Chaer RA, Helton WS. Dieulafoy's disease. J Am Coll Surg 2003;196:290-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdulian JD, Santoro MJ, Chen YK, et al. Dieulafoy-like lesion of the rectum presenting with exsanguinating hemorrhage: successful endoscopic sclerotherapy. Am J Gastroenterol 1993;88:1939-41. [PubMed]

- Yeoh KG, Kang JY. Dieulafoy's lesion in the rectum. Gastrointest Endosc 1996;43:614-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harrison JD, Calatayud A, Thava VR, et al. Massive arterial bleeding from a single rectal vessel. Postgrad Med J 1997;73:303-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yagnik VD. Rectal dieulafoy's lesion: An underrecognized cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. J Dig Endosc 2017;8:202-4. [Crossref]

- Meister TE, Varilek GW, Marsano LS, et al. Endoscopic management of rectal Dieulafoy-like lesions: a case series and review of literature. Gastrointest Endosc 1998;48:302-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eguchi S, Maeda J, Taguchi H, et al. Massive gastrointestinal bleeding from a Dieulafoy-like lesion of the rectum. J Clin Gastroenterol 1997;24:262-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tseng CA, Chen LT, Tsai KB, et al. Acute hemorrhagic rectal ulcer syndrome: a new clinical entity? Report of 19 cases and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum 2004;47:895-903; discussion 903-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abe T, Okada N, Akamatsu H, et al. Successful endoscopic hemostasis of rectal Dieulafoy's ulcer by clipping: aging may be a factor. Dig Endosc 2003;15:64-8. [Crossref]

- Wang M, Bu X, Zhang J, et al. Dieulafoy's lesion of the rectum: a case report and review of the literature. Endosc Int Open 2017;5:E939-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lara LF, Sreenarasimhaiah J, Tang S, et al. Dieulafoy lesions of the GI tract: localization and therapeutic outcomes. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55:3436-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kayali Z, Sangchantr W, Matsumoto B. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to Dieulafoy-like lesion of the rectum. J Clin Gastroenterol 2000;30:328-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajendra T, Chung YF, Ong HS. Rectal Dieulafoy's lesion: cause of massive lower gastrointestinal tract haemorrhage. Aust N Z J Surg 2000;70:746-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Inayat F, Ullah W, Hussain Q, et al. Dieulafoy's lesion of the colon and rectum: a case series and literature review. BMJ Case Rep 2017;2017:220431. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Battista N. A Deceiving Dieulafoy's: A Rare Cause of Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:S1318. [Crossref]

- Fujimaru T, Akahoshi K, Matsuzaka H, et al. Bleeding rectal Dieulafoy's lesion. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;57:922. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nadhem ON, Salh OA, Bazzaz OH. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding due to rectal Dieulafoy's lesion. SAGE Open Med Case Rep 2017;5:2050313X17744982.

- Casella G, Bonforte G, Corso R, et al. Rectal bleeding by Dieulafoy-like lesion: successful endoscopic treatment. G Chir 2005;26:415-8. [PubMed]

- Zamora-Nava LE, Grajales-Figueroa G, Ramirez Polo AI, et al. A rare cause of rectal bleeding. Endoscopy 2018;50:S176.

- Matsuoka J, Taniai K, Kojima K, et al. A case of rectal Dieulafoy's ulcer and successful endoscopic sclerotherapy. Acta Med Okayama 2000;54:281-3. [PubMed]

- Aghenta A, Devgun S, Kothari T. Acute massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding from a rectal Dieulafoy-like lesion in a patient with chronic liver disease. Internet J Gastroenterol 2008;8:1-5.

- Arya PH, Sebastian J, Mangam S, et al. Dieulafoy lesion of rectum: an uncommon pathology not to be missed. Clin Surg 2016;1:1170.

- Katsinelos P, Pilpilidis I, Christodoulou K, et al. Rectal Dieulafoy-like lesion complicated by an ischemic ulcer after successful endoscopic injection-therapy with dilute epinephrine in hypertonic glucose water. Ann Gastroenterol 2001;14:325-8.

- Chiu HH, Chen CM, Mo LR. Rectal Dieulafoy's lesion. Gastrointest Endosc 2004;60:796. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singh V, Mehra S. Rectal Dieulafoy's Lesion: A Rare Cause of Massive Lower GI Bleed. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:S1683-4. [Crossref]

- Jaber TM, Jastaniah AS, Jadkarim GA. Acute Massive Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding From a Dieulafoy Lesion in the Anorectal Junction: A Case Report. Trauma Acute Care 2018;3:3.

- Then EO, Bijjam R, Ofosu A, et al. Rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion: a rare etiology of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2019;13:73-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pineda-De Paz MR, Rosario-Morel MM, Lopez-Fuentes JG, et al. Endoscopic management of massive rectal bleeding from a Dieulafoy's lesion: Case report. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2019;11:438-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khan S, Pinto J, Genao A, et al. Dieulafoy Lesion on the Other Side of the Tract. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:S1127-8. [Crossref]

- Mehta SV, Tayel H, Duarte-Chavez R, et al. Rectal Dieulafoy's Lesion: Hemorrhagic Shock Due to a Rare Cause of Acute Lower GI Bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:S1111-2. [Crossref]

- Nunoo-Mensah JW, Alkari B, Murphy GJ, et al. Rectal Dieulafoy lesions. J Am Coll Surg 2008;206:388-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Apiratpracha W, Ho JK, Powell JJ, et al. Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding from a dieulafoy lesion proximal to the anorectal junction post-orthotopic liver transplant. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:7547-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim HH, Kim JH, Kim SE, et al. Rectal Dieulafoy lesion managed by hemostatic clips. J Clin Med Res 2012;4:439-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amaro R, Petruff CA, Rogers AI. Rectal Dieulafoy's lesion: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum 1999;42:1339-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hotta T, Takifuji K, Tonoda S, et al. Risk factors and management for massive bleeding of an acute hemorrhagic rectal ulcer. Am Surg 2009;75:66-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nozoe T, Kitamura M, Matsumata T, et al. Dieulafoy-like lesions of colon and rectum in patients with chronic renal failure on long-term hemodialysis. Hepatogastroenterology 1999;46:3121-3. [PubMed]

- Malik N, Hussain M, Naqvi SMAA. An unusual Presentation of Dieulafoy’s Lesion as a Cause of Recurrent Lower Gastrointestinal/Rectal Bleeding: A Case Report. Am J Med Case Rep 2017;5:259-61. [Crossref]

- Ruiz-Tovar J, Díe-Trill J, Lopez-Quindos P, et al. Massive low gastrointestinal bleeding due to a Dieulafoy rectal lesion. Colorectal Dis 2008;10:624-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dogan U, Gomceli I, Koc U, et al. Rectal Dieulafoy lesions: a rare etiology of chronic lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Case Rep Med 2014;2014:180230. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gul YA, Jabbar MF, Karim FA, et al. Dieulafoy's lesion of the rectum. Acta Chir Belg 2002;102:199-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berretti D, Marino M, Macor C, et al. Successful endoscopic clipping of rectal Dieulafoy's lesion: case report. Dig Liver Dis 2006;38:1:S211.

- Park JG, Park JC, Kwon YH, et al. Endoscopic management of rectal Dieulafoy's lesion: a case series and optimal treatment. Clin Endosc 2014;47:362-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Natarajan P, Bansal R, Arya V. Uncommon Lesions Commonly Missed: 2 Cases of Evasive Rectal Dieulafoy's Lesions. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;112:S1557. [Crossref]

- Choi YH, Eun JR, Han JH, et al. Massive bleeding from a rectal Dieulafoy lesion in a patient with alcoholic cirrhosis. Yeungnam Univ J Med 2017;34:88-90. [Crossref]

- Nomura S, Kawahara M, Yamasaki K, et al. Massive rectal bleeding from a Dieulafoy lesion in the rectum: successful endoscopic clipping. Endoscopy 2002;34:237. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guy RJ, Ang ES, Tan KC, et al. Massive bleeding from a Dieulafoy-like lesion of the rectum in a burns patient. Burns 2001;27:767-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdelmalek MF, Pockaj BA, Leighton JA. Rectal bleeding from a mucous fistula secondary to a Dieulafoy's lesion. J Clin Gastroenterol 1997;24:259-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jani PG. Dieulafoy's lesion: case report. East Afr Med J 2001;78:109-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Philipose J, Haddad FG, Deeb L. Dieulafoy's Lesion of Ano-Rectum: An Unusual Etiology of Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;113:S1139. [Crossref]

- Hudspath C, Russell D, Eum K, et al. Finding the Dieulafoy's Lesion: A Case of Recurrent Rectal Bleeding in an Immunosuppressed Patient. Case Rep Gastrointest Med 2019;2019:9402968. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cristescu DA, Yuvienco C, Schwartz S. Fatal Henoch-Schönlein purpura in an adult with Dieulafoy lesions. J Clin Rheumatol 2012;18:253-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalman DR, Banner BF, Barnard GF. Rectal Dieulafoy's or angiodysplasia? Gastrointest Endosc 1997;46:91-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tursi A. Rectal Dieulafoy lesion. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2017;41:1-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hokama A, Takeshima Y, Toyoda A, et al. Images of interest. Gastrointestinal: rectal Dieulafoy lesion. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;20:1303. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Esmadi M, Ahmad D, Fisher K, et al. Atypical appearance of a rectal Dieulafoy lesion. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;87:315-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mizukami Y, Akahoshi K, Kondoh N, et al. Endoscopic band ligation for rectal Dieulafoy's lesion: serial endoscopic images. Endoscopy 2002;34:1032. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fukumori D, Sasaki T, Sato M, et al. Massive rectal bleeding from a Dieulafoy's ulcer of the rectum. Int Surg 2004;89:63-6. [PubMed]

- Vandervoort J, Montes H, Soetikno RM, et al. Use of endoscopic band ligation in the treatment of ongoing rectal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;49:392-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Önem S, Htway Z, Cengiz O, et al. Dieulafoy Lesion In The Rectum: A Case Report. World J Gastroenterol Hepatol Endosc 2019;1:1-13.

- Goldkamp W, Goldberg R, Patel K. Rare Case of GI Bleeding: Rectal Dieulafoy’s Lesion. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:S414. [Crossref]

- Wells S, Suryawala K, Morris J. Looks Like, Sounds Like, But….A Rectal Dieulafoy? Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:S413. [Crossref]

- Stark ME, Gostout CJ, Balm RK. Clinical features and endoscopic management of Dieulafoy's disease. Gastrointest Endosc 1992;38:545-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reilly HF 3rd, al-Kawas FH. Dieulafoy's lesion. Diagnosis and management. Dig Dis Sci 1991;36:1702-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoshikumi Y, Mashima H, Suzuki J, et al. A case of rectal Dieulafoy's ulcer and successful endoscopic band ligation. Can J Gastroenterol 2006;20:287-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee YK, Bair MJ, Chen HL, et al. A case of massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding from a rectal Dieulafoy lesion. Adv Dig Med 2015;2:108-10. [Crossref]

- Kiran S, Jain A, Gupta D, et al. Rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion detected using MRI of pelvis – first of its kind. International Journal of Clinical & Medical Imaging 2016;3:1000491.

- Chen YY, Yen HH. Massive bleeding from a rectal dieulafoy lesion: combined multidetector-row CT diagnosis and endoscopic therapy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2008;18:398-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaneko M, Nozawa H, Tsuji Y, et al. Multidetector-row computed tomography and colonoscopy for detecting a rectal Dieulafoy lesion as a source of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2018;12:202-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vila JJ, Perez-Miranda M, Basterra M, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided therapy of a rectal Dieulafoy lesion. Endoscopy 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E84-5.

- Goldenberg SP, DeLuca VA Jr, Marignani P. Endoscopic treatment of Dieulafoy's lesion of the duodenum. Am J Gastroenterol 1990;85:452-4. [PubMed]

- Jeon HK, Kim GH. Endoscopic Management of Dieulafoy's Lesion. Clin Endosc 2015;48:112-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yadav D, Nambiar R, Hertan HI. Rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion presenting as massive lower GI bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:S254. [Crossref]

- Lee WS, Lee SH, Noh DY, et al. Rectal Dieulafoy's Lesion as a cause of Massive Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc 2002;25:411.

- Slim R, Yaghi C, Honein K, et al. Rectal Dieulafoy's lesion. Report of two cases treated successfully by endoscopic means. J Med Liban 2006;54:38-41. [PubMed]

- Kim HK, Kim JS, Son HS, et al. Endoscopic band ligation for the treatment of rectal Dieulafoy lesions: risks and disadvantages. Endoscopy 2007;39:924-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fuchizaki U, Kamata T, Miyamori H. Endoscopic management of life-threatening rectal Dieulafoy-like lesions. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65:AB264. [Crossref]

- Ahn DW, Lee SH, Park YS, et al. Hemostatic efficacy and clinical outcome of endoscopic treatment of Dieulafoy's lesions: comparison of endoscopic hemoclip placement and endoscopic band ligation. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;75:32-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ali M, Ul Haq T, Salam B, et al. Treatment of nonvariceal gastrointestinal hemorrhage by transcatheter embolization. Radiol Res Pract 2013;2013:604328. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee CS, Widjaja D, Siegel M, et al. Endoscopic band ligation of a rectal Dieulafoy's lesion. J Clin Gastroenterol 2004;38:828-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dobson CC, Nicholson AA. Treatment of rectal hemorrhage by coil embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 1999;22:143-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nishimuta Y, Tsurumaru D, Komori M, et al. A case of rectal Dieulafoy's lesion successfully treated by transcatheter arterial embolization. Jpn J Radiol 2012;30:176-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Atallah S, Albert M, Debeche-Adams T, Larach S. Transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS): applications beyond local excision. Tech Coloproctol 2013;17:239-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Inayat F, Hussain A, Yahya S, Weissman S, Sarfraz N, Faisal MS, Riaz I, Saleem S, Saif MW. Rectal Dieulafoy’s lesion: a comprehensive review of patient characteristics, presentation patterns, diagnosis, management, and clinical outcomes. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;7:10.