Rare gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): omentum and retroperitoneum

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) typically originate from interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC), which are pace-maker cells that control gastrointestinal track (GIT) peristalsis and the only cells that exhibit the KIT or CD34 immunochemical positive reaction in the GIT, which is the diagnostic hallmark of a GIST (1). The tumors can occur anywhere that these cells exist in the GIT, including the stomach (60–70%, which has a preferable prognosis), ileum and jejunum (25–30%), colon and rectum (5–15%), duodenum (5%) and esophagus (2%) (2,3). Some GISTs occur outside the digestive tract, such as in the omentum or retroperitoneum. These types are called extra-GISTs (EGISTs) (4,5). Other less frequent anatomical locations have been reported as primary sites, such as the liver (6), mediastinum (7), pharynx (8) and gall bladder (9). ICC-like cells, which are KIT-positive mesenchymal cells, have been reported in the omentum (10). Similarly, ICC-like cells have been identified in many other organs, such as the urinary bladder, gall bladder, omentum, uterus, prostate and myocardium (11); thus, it is reasonable to assume that EGISTs originated from a common precursor that differentiated into ICC-like cells outside of the GIT. Therefore, EGISTs may theoretically arise from outside of the GIT. Miettinen et al. first defined soft tissue tumors, which originate outside of the GIT and present clinicopathological features and molecular characteristics similar to those of GISTs, as EGISTs (4). While the clinicopathological and biological features and prognosis of conventional GISTs are widely known, those of EGISTs have not been thoroughly investigated due to their sparsity.

Incidence

While the annual incidence of GISTs is estimated at 10–15 per 1 million in the general population (12), the incidence of EGISTs is reported to be approximately 10% or less of all GISTs. Miettinen et al. found that the incidence of EGISTs accounted for approximately 5–10% of GISTs and approximately 4–7% of soft tissue tumors in the abdominal cavity (4). Castillo-Sang M et al. showed that EGISTs accounted for 4.5% of all stromal tumors (22/486), with a male to female ratio of 1.4:1 and a median onset age of 45.5 years (13). Du et al. reported the incidence of EGISTs as 15 out of 141 (10.6%) cases (14). Cho et al. (15) also described similar incidences of the disease (10.1%). In a report of SEER data, 323 out of 2812 (11.5%) cases were found to be EGISTs (16).

Occurrence sites

Cho et al. (15) also showed the most common site for these tumors was the mesentery (45.1%) followed by intra-abdominal (34.3%), pelvis (9.8%), retroperitoneum (3.9%) and abdominal wall (3.9%). Zhou et al. reported that the incidence of tumors in the mesentery was 50% (11/22), in the retroperitoneum was 36.4% (8/22) and in the omentum was 13.6% (3/22) (17). It has been reported that EGISTs are often found in the mesentery, omentum and retroperitoneum, and they can also occur in the pancreas, bladder and female reproductive system (18).

Pathology

EGISTs are a group of rare tumors with similar histology and immunohistochemical features as conventional GISTs, occurring outside the GIT, with a majority of them in the omentum and mesentery or in the retroperitoneum (4,19,20). Like their digestive counterparts, most omental tumors are typically positive for KIT and less consistently for CD34, positive for α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and negative for desmin and S100 protein (4). These tumors have low mitotic activity and, similarly to GISTs, present as elongated spindle cells, epithelioid cells or mix cells with high cellularity (21). Analyzing 48 EGISTs (40 omental and mesenteric and 8 retroperitoneal), Reith et al. found that the tumors expressed KIT 100%, CD34 50%, neuron-specific enolase (NSE) 44%, α-SMA 26%, desmin 4% and S100 protein 4% (5).

Approximately two-thirds of patients with a conventional GIST have a c-kit mutation at exon 11 (22). Although the ratio of c-kit and PDGFRA gene mutations is similar to ordinary GISTs, their frequency is lower than conventional GISTs. The incidence of EGISTs mutated at exon 11 is reported to be approximately 40–50% (14,19). As this mutation is expected to have a good response to imatinib, a greater number of mutation analyses for EGISTs are required. To our best knowledge, there are two definite reports of EGIST responding to imatinib (23,24). Exon 11 mutation was indicated in one of the reports (24).

Malignant potential

The clinical outcomes of EGISTs are not fully understood due to their sparsity. However, compared with a conventional GIST, an EGIST is considered to have a less favorable prognosis (5,15,16). This is because EGISTs are frequently accompanied by unfavorable prognostic factors, such as high mitotic indices, large size and distant metastasis including lymph node involvement. Zhou et al. (17) reported on the survival of EGIST patients. Comparing the survival of conventional GIST patients, the 1-, 3- and 5-year overall survival rates of EGIST patients were 91.7%, 61.1% and 48.9%, respectively; the 1-, 3- and 5-year recurrence-free survival rates were 72.2%, 28.9% and 19.3%, respectively. The overall survival rate of EGIST patients was significantly lower than that of conventional GIST patients (with 1-, 3- and 5-year overall survival rates of 94.0%, 88.1% and 82.4%, respectively); however, EGIST and conventional GIST patients did not show a statistically significant difference in recurrence-free survival. Other investigators have shown that the prognosis of an EGIST is less favorable (5,15). Zhou et al. (17) speculated that the significant differences between the two groups in survival might be related to the following two points. First, tumor size is thought to be an important factor affecting the prognosis of stromal tumors. The median tumor diameter of an EGIST is typically greater than that of a GIST, which may be due to available space at occurrence sites; thus, the clinical symptoms occur only when the tumor size becomes large, leading to the observation that EGISTs are relatively larger. Second, compared with a typical GIST, an EGIST does not affect the digestive tract; therefore, it is rare to identify early symptoms, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, that are observed in GISTs. This is also an important factor causing the relatively larger size and more advanced staging when an EGIST is discovered.

Prognostic factors

Tumor size, mitotic index and primary tumor sites are important factors affecting the prognosis of GISTs; therefore, they have been included in the risk grading system for GISTs. A high mitotic index [5/50 high-power field (HPF)] or a high Ki-67 labeling index (10%) were associated with poor prognosis in the case of an EGIST (19). Tumor size is an important prognostic factor in both the National Institute of Health (NIH) and the Armed Forces Institutes of Pathology criteria (25). EGISTs are often a large size due to their anatomic site which has enough space to grow before producing symptoms. Guye et al. reported that tumor size was not an adverse prognostic factor in a multivariate survival analysis of a large GIST cohort composed of 2,489 patients (88.5%) with GISTs and 323 patients (11.5%) with EGISTs (16). Therefore, tumor size might not be associated with adverse outcomes because most of EGISTs were found a large size. Another explanation is that tumor size itself may not express the biological characteristics of an EGIST because the tumor size has different clinical implications at different anatomical sites (3). Further examination should be required to the prognostic role of tumor size in EGISTs. Therefore, a grading system for conventional GIST using a combination of mitotic index and tumor size may not be completely applicable for EGISTs.

Difficult diagnosis

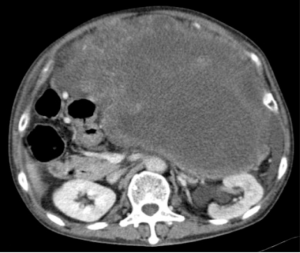

Agaimy and Wünsch reported that tumors labeled initially as primary EGISTs were instead GISTs (26). Acritical reevaluation of the surgical report and a careful search for original muscular tissue from the gut wall in the tumor pseudocapsule of 14 EGISTs, made it possible to reclassify most of these cases as either GISTs with extramural growth (8/14) or as metastases from a GIST (3/11). This study emphasized the focal attachment or adhesions to the gut wall that must be documented intraoperatively and the paramount role of the pathologist in searching for any residual muscle tissue in the tumor pseudocapsule. The clinical presentation of EGISTs depends on the primary location and dimensions. In very large abdominal tumors, the visceral origin is almost impossible to determine (Figure 1).

Conclusions

Compared with conventional GIST patients, EGIST patients have a younger onset age, larger tumor size and poorer prognosis. The clinical symptoms of EGISTs are often manifested as common digestive symptoms. Because it does not typically affect the GIT, an EGIST rarely causes gastrointestinal bleeding, obstruction or other typical clinical manifestations. A survival analysis showed that the primary tumor site and mitotic indices are important factors, but tumor size is controversial in affecting the prognosis of EGIST patients. Due to the low incidence of EGISTs, multi-center collaborative investigations combining basic research with clinical studies are required to expand the sample size and further study the biological characteristics of EGISTs.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Sircar K, Hewlett BR, Huozinga JD, et al. Interstitial cells of Cajal as precursors of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:377-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Emory TS, Sobin LH, Lukes L, et al. Prognosis of gastrointestinal smooth-muscle (stromal) tumors: dependence on anatomic site. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:82-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: pathology and prognosis at different sites. Semin Diagn Pathol 2006;23:70-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miettinen M, Monihan JM, Sarlomo-Rikala M, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors/smooth muscle tumors (GISTs) primary in the omentum and mesentery: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:1109-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reith JD, Goldblum JR, Lyles RH, et al. Extragastrointestinal (soft tissue) stromal tumors: an analysis of 48 cases with emphasis on histologic predictors of outcome. Mod Pathol 2000;13:577-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hu X, Forster J, Damjanov I. Primary malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2003;127:1606-8. [PubMed]

- Lee JR, Anstadt MP, Khwaja S, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the posterior mediastinum. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2002;22:1014-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siddiq MA, East D, Hock YL, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumour of the pharynx. J Laryngol Otol 2004;118:315-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park JK, Choi SH, Lee S, et al. Malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the gallbladder. J Korean Med Sci 2004;19:763-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sakurai S, Hishima T, Takazawa Y, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors and KIT-positive mesenchymal cells in the omentum. Pathol Int 2001;51:524-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Min KW, Leabu M. Interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) and gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST): facts, speculations, and myths. J Cell Mol Med 2006;10:995-1013. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mucciarini C, Rossi G, Bertolini F, et al. Incidence and clinicopathologic features of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. A population-based study. BMC Cancer 2007;7:230. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Castillo-Sang M, Mancho S, Tsang AW, et al. A malignant omental extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor on a young man: a case report and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol 2008;6:50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Du CY, Shi YQ, Zhou Y, et al. The analysis of status and clinical implication of KIT and PDGFRA mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). J Surg Oncol 2008;98:175-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cho MY, Sohn JH, Kim JM, et al. Current trends in the epidemiological and pathological characteristics of gastrointestinal stromal tumors in Korea, 2003-2004. J Korean Med Sci 2010;25:853-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guye ML, Nelson RA, Arrington AK, et al. The prognostic significance of extra-intestinal tumor location for primary nonmetastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors. In: 2012 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium. J Clin Oncol 2008;30:2. [Crossref]

- Zhou J, Yan T, Huang Z, et al. Clinical features and prognosis of extragastrointestinal stromal tumors. Int J Clin Exp Med 2016;9:16367-72.

- Krokowski M, Jocham D, Choi H, et al. Malignant extragastrointestinal stromal tumor of bladder. J Urol 2003;169:1790-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto H, Oda Y, Kawaguchi K, et al. c-kit and PDGFRA mutations in extragastrointestinal stromal tumor (gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the soft tissue). Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:479-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gun BD, Gun MO, Karamanoglu Z. Primary stromal tumor of the omentum: report of a case. Surg Today 2006;36:994-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Sarlomo-Rikala M. Immunohistochemical spectrum of GISTs at different sites and their differential diagnosis with a reference to CD117 (KIT). Mod Pathol 2000;13:1134-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corless CL, Barnett CM, Heinrich MC. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: origin and molecular oncology. Nat Rev Cancer 2011;11:865-78. [PubMed]

- Rediti M, Pellegrini E, Molinara E, et al. Complete pathological response in advanced extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor after imatinib mesylate therapy: a case report. Anticancer Res 2014;34:905-7. [PubMed]

- Joyon N, Dumortier J, Aline-Fardin A, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) presenting in the liver: Diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic issues. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goh BK, Chow PK, Yap WM, et al. Which is the optimal risk stratification system for surgically treated localized primary GIST? Comparison of three contemporary prognostic criteria in 171 tumors and a proposal for a modified Armed Forces Institute of Pathology risk criteria. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:2153-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agaimy A, Wünsch PH. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: a regular origin in the muscularis propria, but an extremely diverse gross presentation. A review of 200 cases to critically re-evaluate the concept of so-called extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2006;391:322-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Sawaki A. Rare gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): omentum and retroperitoneum. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2:116.